The Human at the Center – Fritz Wotruba at Belvedere 21

To mark the 50th anniversary of his death, the museum is presenting an impressive exhibition featuring 24 sculptures by the Austrian sculptor – in dialogue with works by international contemporaries. A text by Sabine B. Vogel.

Fritz Wotruba, Large Reclining Figure, 1951–53 Belvedere, Wien, 2019 Dauerleihgabe Wiener Konzerthausgesellschaft, Foto: Johannes Stoll / Belvedere, Wien

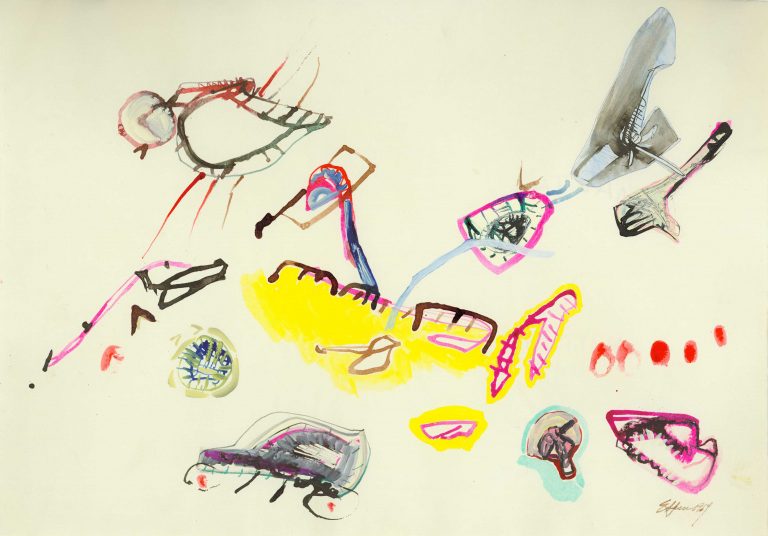

Sitting, standing, lying down—these three positions are among the fundamental themes of sculpture. In the 1930s, Fritz Wotruba celebrated international success with his variations on these themes. Twenty-four such figures, often life-size, from the years 1938–1974 are now on display in an outstanding exhibition at Belvedere 21. Just in time for the 50th anniversary of his death, the museum aims to highlight his “worldwide exhibition activity, artistic network, and reception” through a dialogue presentation featuring 15 sculptures by his contemporaries. This is certainly necessary, because although he was once celebrated as a pioneer of post-war modernism in Austria, his work has been perceived at most only regionally in recent decades.

Born in Vienna in 1907, the sculptor enjoyed great success at the Venice Biennale in the 1930s, participated twice in documenta, and exhibited his sculptures in a total of 70 solo exhibitions, including 50 international ones, from 1931 until his death in 1975. In the mid-1950s, his work toured the US, and in 1958 he signed an exclusive sales contract with the New York gallery Fine Arts Associates. But after his death in 1975 and with the emergence of new artistic avant-gardes, his concept of sculpture was increasingly regarded as formalistic and too academic. This was because Wotruba consistently adhered to the motto he formulated in 1959: “The human figure continues to be the inspiration for my work; it stands at the beginning and will stand at the end.”

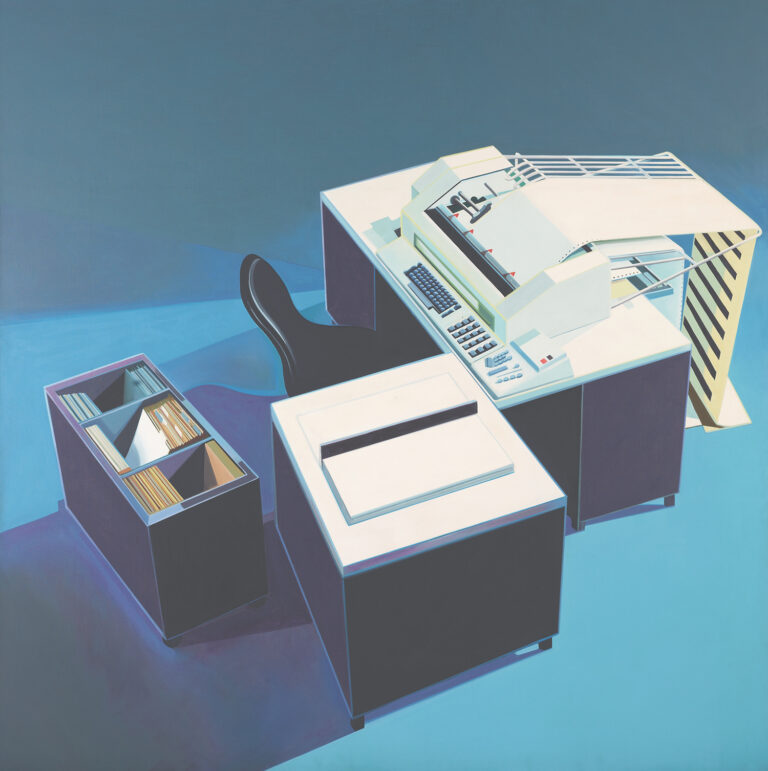

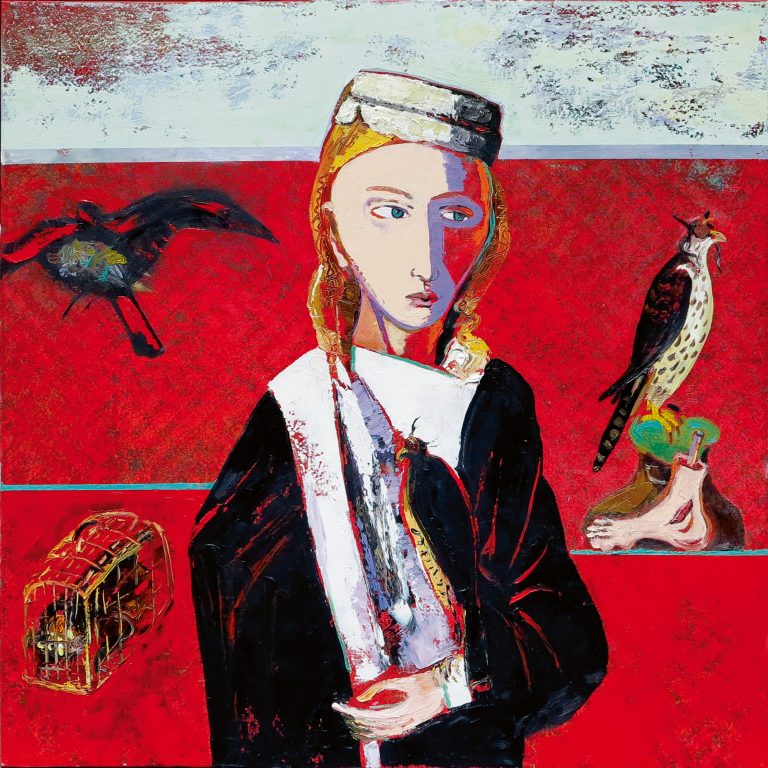

Exhibition view "Wotruba International", Belvedere 21. Photo: Johannes Stoll / Belvedere, Vienna

This motto also applies to the current exhibition at Belvedere 21.The outstanding exhibition architecture by next ENTERprise Architects lets us wander through a sculpture park alongside works by Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, British sculptor Barbara Hepworth, and US artist Louise Nelson.

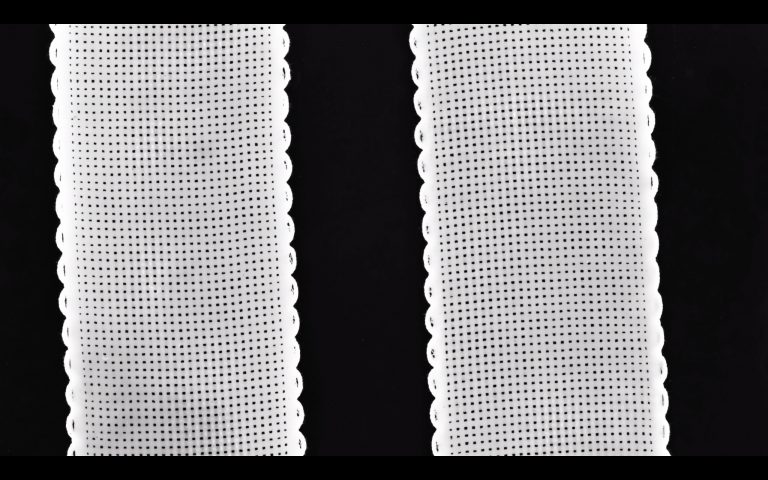

They all rest on pedestals made of honeycomb cardboard. The elements, sometimes stacked in pyramid shapes, are not only an aesthetic choice, but above all a structural one. This allows the sometimes enormous weight of the works to be cushioned by air and distributed over a larger area. Sometimes grouped closely together, influences, adoptions, distinctions, and above all developments can be studied. The richness of form in these sometimes more, sometimes less abstract, human-related sculptures made of stone or bronze is fascinating! Not least, the historical distance helps us to re-appreciate their artistic qualities – especially in times of the current concept of art, which levels all boundaries.

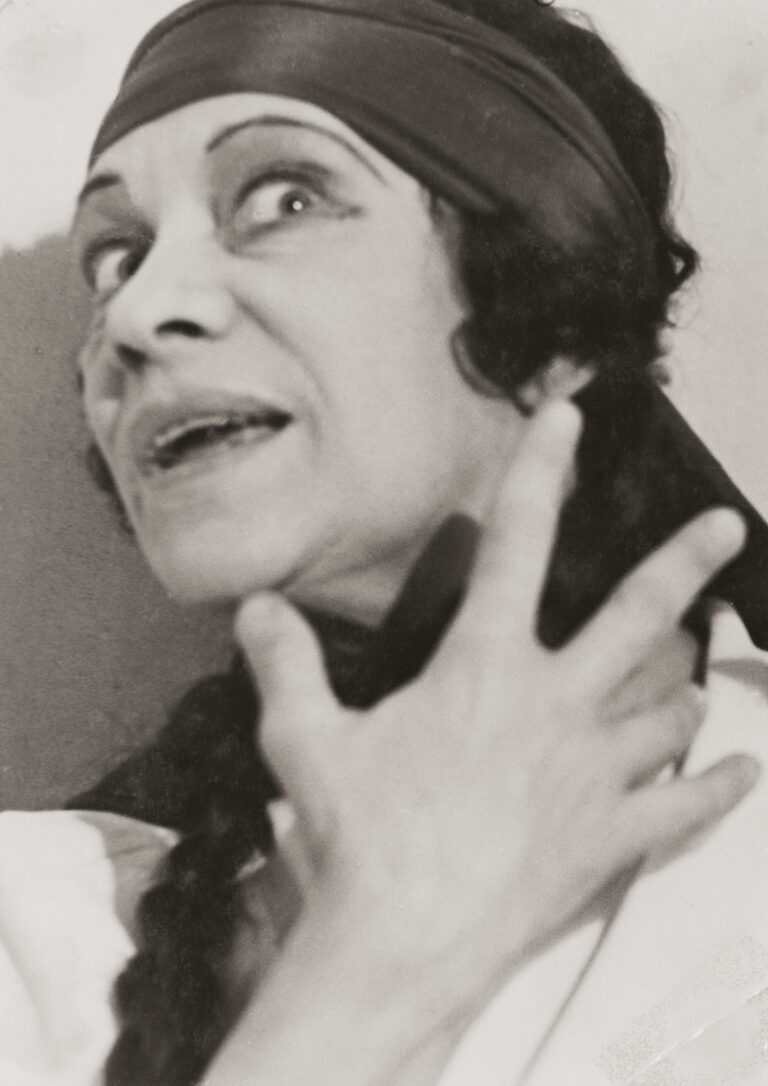

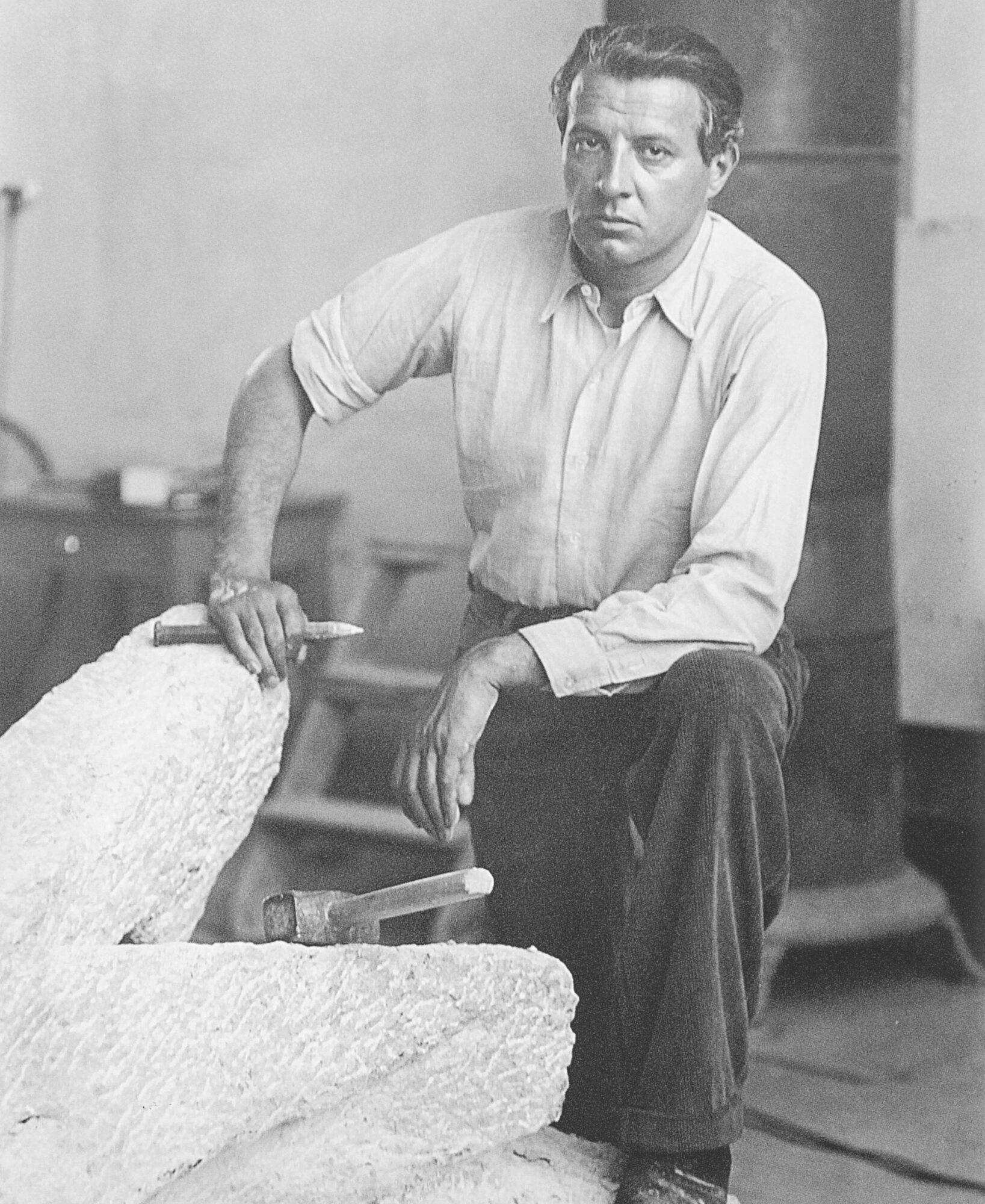

Fritz Wotruba in his studio in Vienna, 1947/48. Photo: Ernst Hartmann / Bildrecht, Vienna 2025

However, there is something irritating about this concentrated presence of Wotruba’s works, which are celebrated as “modern art.” Did the artist not seek out the young avant-garde artists during his trip through the US? Donald Judd did not exhibit his rectangular, wall-mounted boxes until 1963, and Carl Andre followed four years later with his steel plates, which lay directly on the floor of the Guggenheim Museum. But the idea of radical abstraction was already emerging in the 1950s; after all, Alexander Calder had already presented a new concept of sculpture in the 1930s with his kinetic sculptures, which he later called mobiles. Why did such works not influence Wotruba’s work—was it a lack of information? Was Wotruba unaware of the development of minimalism, or did it simply contradict his motto of putting people at the center? If one studies his models for churches such as the Carmelite convent in Steinbach from 1956 or visits his Church of the Holy Trinity on the Georgenberg in Vienna-Mauer, which was inaugurated in 1976 and was vehemently rejected at the time, influences can certainly be suspected – this could be the subject of a future exhibition that sheds new light on the (all too) long-held assumption that Austrian post-war modernism was backward.

Fritz Wotruba, Large Standing Man, 1974 Belvedere, Vienna. Photo: Johannes Stoll / Belvedere, Vienna